|

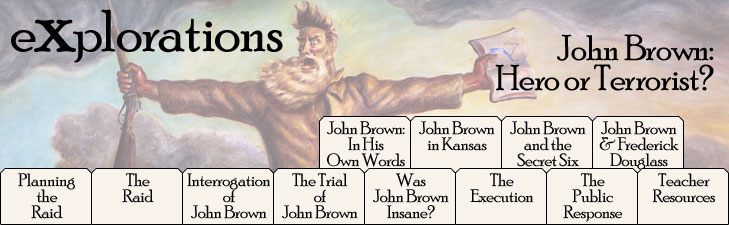

John

Steuart Curry, The Tragic Prelude (Detail),

1937-42, Kansas State Capitol, Topeka.

Background

Between

1819 and 1860, the critical issue that divided the North and

South

was the extension of slavery in the western territories. The

Compromise of 1820 had settled this issue for nearly 30 years

by drawing a dividing line across the Louisiana Purchase that

prohibited slavery north of the line, but permitted slavery south

of it.

The

seizure of new territories from Mexico reignited the issue. The

Compromise of 1850 attempted to settle the problem by admitting

California as a free state but allowing slavery in the rest of

the Mexican cession. Enactment of the Fugitive Slave Law as part

of the Compromise exacerbated sectional tensions.

The

question of slavery in the territories exploded once again when

Senator Stephen A. Douglas proposed that Kansas and Nebraska territories

be opened to white settlement and that the status of slavery be

decided according to the principle of popular sovereignty. The

Kansas-Nebraska Act convinced many Northerners that the South

wanted to open all federal territories to slavery and brought

into existence the Republican party, committed to excluding slavery

from the territories.

Sectional

conflict was intensified by the Supreme Court’s Dred

Scott decision, which declared that Congress could not exclude slavery

from the western territories and by the abolitionist John Brown’s

raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

John

Brown

In

1856, three years before his celebrated raid on Harpers Ferry,

John Brown, with four of his sons and three others, dragged five

unarmed men and boys from their homes along Kansas's Pottawatomie

Creek, and hacked and dismembered their bodies as if they were

cattle being butchered in a stockyard. Two years later, Brown

led a raid into Missouri, where he and his followers killed a

planter and freed eleven slaves. Brown's party also absconded

with wagons, mules, harnesses, and horses – a pattern of

plunder that Brown followed in other forays. During his 1859 raid

on Harpers Ferry, seventeen people died. The first was a black

railroad baggage handler; others shot and killed by Brown's men

included the town's popular mayor and two townsfolk.

Nearly a century and a half after his execution, John Brown remains

one of the most fiercely debated and enigmatic figures in American

history.

Almost every American knows at least some of the words of the

song “John Brown’s Body.”

In

a speech at Harpers Ferry in 1932, W.E.B. Du Bois captured for

all time this unsettling meaning of Brown's legacy:

Some people have the idea that crucifixion consists in

the punishment of an innocent man. The essence of crucifixion

is that men are

killing a criminal, that men have got to kill him ... and yet

that the act of crucifying him is the salvation of the world.

John Brown broke the law; he killed human beings... . Those

people who defended slavery had to execute John Brown although

they knew that in killing him they were committing the greater

crime. It is out of that human paradox that there comes crucifixion.

Read

more about the

Raid on Harpers Ferry in our Online Textbook

(This link opens in a new window; close that window to return

to this page.)

Brown's

raid on Harpers Ferry poses fundamental questions.

- Why

did John Brown, alone among northern abolitionists, choose violence

as the way to end slavery?

- What

impact did he have on the coming of the Civil War?

- Was

he successful in achieving his goals, was he a failure, or was

his legacy more ambiguous?

- Could

slavery have been abolished in this country without violence?

|